Chain Reactions and Atomic Reactors

Atomic Energy, we made it.

Introduction

So now we’ve covered a bit of information on neutrons and how they work. At this point, let’s plunge forward into a pile. An atomic pile. Or a uranium maschine if you’re a Jerry. So what is a nuclear reactor and why do we care? Well aside from their semi-practical applications in electricity and isotope production a nuclear reactor is in principle just a slowed down atomic bomb. Now hippies are gonna jump all over that and start shrieking about the 50 year old plant humming away up the road, and while I’ll be to first to admit that plant most likely has some problems, it’s not a ticking time bomb. It’s more a frontal assault on your wallet, but that’s a rant for another time.

A nuclear reactor is simply a device that can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. Fissionable material is set up in such a way that fission reactions happen at a essentially constant rate, releasing energy in the process. Reactors sustain this process in a very slow, controlled way. Fission bombs do this, as we shall see in future installments, in a very, very fast no breaks sort of way. By understanding the reactor the principles of a bomb become that much more straightforward. Reactors are important because they are also atomic kilns that can be used to “bake” fissionable isotopes; plutonium-239 and uranium-233 out of uranium-238 and thorium-232 respectively. A reactor is centered around a core which is the region of the reactor where the nuclear fuel lives and the fission chain reaction takes place.

The first ever nuclear reactor assembled by human beings1 was build under a sports field at the University of Chicago in 1942 by a team of chemists and physicists led by Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard2. Though there had been discussions towards constructing a reactor since 1940, the declarations of war on the United States by the Anti-Comintern Pact powers in 1941 gave impetus for nuclear science research. The Manhattan Project, under whose auspices this first reactor known as Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was built, aimed to produce nuclear bombs for the war effort.

Szilard had originally trained as a theoretical physicist and had been thinking about the possibilities of nuclear chain reactions since the early 1930’s. He is credited with first theorizing the concept and had spent part of the 1930’s looking for possible candidates for such a reaction. He was also involved in helping refugee academics escape SS death squads and was himself a refugee, working in the United Kingdom on biological and nuclear physics research which kept him busy. He was not involved in the Strassman, Mietner, Hahn and Frish fission work but immediately grasped the significance. A chain reaction was most likely possible using uranium as it gave off neutrons in the fission process. The question was how could a self sustaining chain reaction be created?

Neutron Multiplication

Szilard had performed experiments in 1939 that indicated that approximately 2.3 neutrons were produced for every fission of U-235 at thermal energies3. That is enough to sustain a chain reaction. In order to make a chain reaction, you need a mass of fissionable nuclei and a means of ensuring that most of the neutrons produced by a given fission event induce a subsequent fission event. Herding neutronic cats, essentially. If too many neutrons are lost or captured or otherwise don’t cause a fission reaction, the chain reaction dies off. No chain reaction means your reactor sits inert. This neutron reproduction is defined by a dimensionless quantity called the reproduction factor, k. k is a ratio between the number of neutrons in a given generation n and the number of neutrons in the generation immediately preceding (n - 1). If k < 1 the reaction damps itself out like kindling trying to catch a wet log. If k = 1 the reaction is self sustaining meaning that the reaction rate is constant. If k > 1 then you have an exponential increase in the reaction rate. If your building a reactor you want to aim for k = 1, and if you’re making a bomb you want to aim for k >> 1 as we’ll see. You can also think of k as reflecting the net number of neutrons produced in a given fission event after the rest are captured or taken away. If k = 1 then you have exactly one neutron to trigger one more fission event, keeping the reaction rate constant. With a smaller k you have fewer neutrons per event and with a larger k you have more, allowing for exponential increases.

Let’s look at an example. If we have a k value of 0.5 and if we start with 1000 neutrons, how many will we have after n = 10 generations? We’re dealing with exponentials here so,

When k = 0.5 we can see the rapid decrease of neutrons after 10 generations.

If we assume k = 1 we can see that the neutron count holds constant.

If we go to k = 1.01 we can see a noticeable amount of growth, around 10 percent.

If k is increased or the number of generations is increased, the number of neutrons and by extension the reaction rate increases. But what determines the k factor to begin with?

It’s a function of the neutrons in the reactor. After a fission, a neutron really only has three possible life paths. 1) to collide with a nucleus and be scattered, 2) to cause another fission and 3) to be captured by a nucleus. In a reactor we can assume the material is large enough and the time scales are long enough that scattered nuclei will eventually reach another nuclei and will either be captured or induce a fission. As such we really only have to worry about fission and capture processes and can sum the scattering and capture cross sections4.

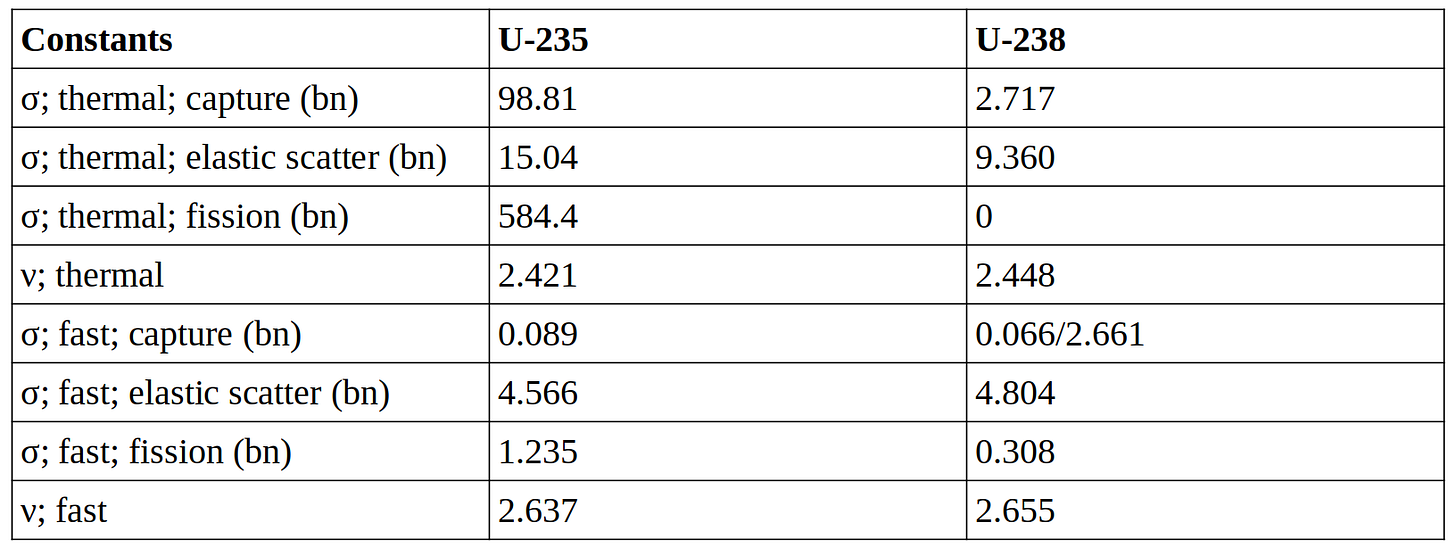

So what determines the likelihood of a fission or capture event of a given neutron at a given energy? The cross section! The k factor is ultimately function of cross sections. For this very simplified picture we want to keep four cross sections in mind, the capture and fission cross sections for uranium 235 and 238 at thermal energies. These values are taken from Reed, 20115.

A note on the fast capture cross section of U-238; 0.066 barns is the actual value, but an inelastic collision with a U-238 nucleus causes the neutron energy to drop to a point where it would have a larger chance of capture. As such the effective cross section is equal to the inelastic scattering cross section (2.595 barns) plus the capture cross section of U-238.

The variable ν represents the average number of neutrons emitted per fission. Note that at thermal energies the ν for U-238 is effectively zero due to the extremely low cross section. You can in theory have a fission event but the probability is so low that it is effectively zero.

There is one more variable to be considered, that of the enrichment factor F. F is the ratio of the amount of U-235 in a given mass of uranium.

So to compute the k factor we need to first find the relevant cross sections for our two isotopes. First find the total cross sections for the two isotopes we’re considering6.

Once we get the cross section totals, we multiply them by the enrichment factor to find the total cross section.

Let’s consider this for natural uranium. For natural uranium the enrichment factor F = 0.0073 and given that fission neutrons have an energy of ~2 MeV we will use our 2 MeV fast fission cross section values.

Now we have to find the number of secondary neutrons produced by each fission channel; one for U-235 and one for U-238 and sum them. This is our k factor and is where we use our values for ν, the average number of neutrons produced per fission event. As an idealized equation k is the ratio of the fission and total cross sections times the number of neutrons produced per fission.

This is an ideal assumption because in an actual reactor you have other isotopes with different capture cross sections, neutron loss out of the core and a host of other complicating factors.

Considering our two channels with different isotopes we find a slightly more complex equation.

Once again we’re assuming natural uranium and fast neutrons so find the following value for k.

This is why no matter how much natural uranium you have, it will not undergo a chain reaction with fast neutrons. The k factor is below 1 and so the reaction will damp itself out. To get one going requires either a higher enrichment factor or thermal energy neutrons. That requires the addition of a moderator. We will have much more to say about moderation and its difficulties below but for now, let’s consider the k factor assuming thermal energy neutrons of ~0.025 eV7.

If you could thermalize all the fission neutrons without incurring any capture losses in the moderator or U-238 (an essentially impossible task in the real world) you would get a k value well above 1 making a chain reaction a possibility. The other approach is simply to enrich the amount of U-235 present in the fuel. Modern power reactors use both of these approaches, enriching the amount of fuel to around 3% U-235 while also moderating the neutrons. Typically normal water is used as a moderator. Reactors have been built using natural uranium without enrichment with various moderators, typically graphite or heavy water8 . Graphite and natural uranium were used in the first ever nuclear reactor built in Chicago that I mentioned above. Reactors have also been designed using fast neutrons alone to drive a chain reaction but they use highly enriched fuels and exotic coolants; Typically a liquid metal like sodium is used which poses many operational difficulties so they’re really only used for experimental research.

The Four Factor Equation

So now that the effects of energy dependent cross sections are a little clearer we can begin to add terms to our multiplication function. The multiplication function typically has four terms, hence ‘Four Factor’. Basically these terms are modifications of the baseline reproduction factor. Each one accounts for more complicating factors in the reactor core design. The first, which we explored above is η the reproduction factor. To that we multiply three additional terms which account for various conditions in the reactor. We’ll take these one at a time.

You may be wondering about the infinity symbol affixed to our k; It means that this function assumes there is no neutron leakage or that the reactor is ideally infinite in size so all the available neutrons get eaten up. The result is good enough for back of the envelope calculations but if you do factor in neutron leakage out of the core you get a smaller value called the effective multiplication factor, keff.

To calculate this we have to introduce a concept we’ve seen before though I didn’t identify it by name at the time. The macroscopic cross section which is simply a cross section value multiplied by the number density, n9. The enrichment method we did above is still effective, but the macroscopic cross section gives a more intuitive feel for what’s going on when we consider reactors.

Where I is just a place holder for any interaction (fission, capture, elastic scattering and so on). The macroscopic cross section has units of #atoms interact/cm which means it tells you the probability of a neutron interacting with a nucleus for every centimeter it travels through a given material. The reason we use macroscopic cross sections instead of microscopic cross sections for actual reactors is simply a matter of convenience. When dealing with macro-scale objects like nuclear reactors it’s useful to think of things in terms of interactions per centimeter of reactor than interactions per nucleus.

Looking at η, the neutron multiplication factor in the new macroscopic cross section perspective is gives us the following:

I’ll walk us through the rest of these terms and then do a really rough example.

The Thermal Utilization Factor, f

First we have f, the thermal utilization factor. This is simply a ratio of the number of neutrons that are absorbed by the fuel and the number of neutrons absorbed in total. In practice this simply relates the neutrons that make it to the fuel, either to be captured or cause fission over all the other possible neutron consumption paths in the fuel, in the moderator, in any structural elements and so on.

In the simplest case of the reproduction factor we can assume a homogeneous reactor. A homogeneous reactor is just a convoluted way of saying that the moderator and nuclear fuel are a contiguous mass. In real life reactors like this are very rare, but some like the molten salt reactors mentioned above fit the pattern. There are also some research reactors that use uranium salts dissolved in water and the solution is both fuel and moderator. In any case our function for f then looks like this.

The subscripts c and f represent capture and fission respectively. Fission and absorption are the events that consume neutrons in the fuel; their summation is the total macroscopic cross section in the nucleus. The denominator contains all the possible absorption paths so capture and fission in the fuel are considered as is capture in the moderator. Because the fuel and moderator have the same volume and the neutron flux in the system can be considered a constant. As can be seen, this value will always be less than one as you’re always going to lose neutrons to non-fuel components in a reactor, even if it’s just the moderator.

Most reactors aren’t homogeneous though and have separate fuel, moderators, structural elements and so on. These all have discrete volumes which influence how many thermal neutrons they absorb. Still though, we’ll make a few simplifying assumptions. Our reactor will have fuel, a moderator and the possibility for a control rod. Like the homogeneous reactor we’ll also assume a constant neutron flux through the core, though in reality this is not accurate but a discussion of neutron transport requires a post of its own. A control rod is a piece of a material with a very high neutron capture cross section that is inserted into the core to control the fission rate. Typically a material containing boron or cadmium is used as they have massive thermal capture cross sections. By placing it into the core the value of f decreases, which in turn decreases k. The fission chain reaction can’t be sustained because too many neutrons are slurped up by the control rod. Considering these three elements give us the following:

The V terms refer to the ratio of the various reactor component volumes to the total volume of the reactor. For example consider the ratio of the fuel to the rest of the reactor.

We care about the volume ratio for the simple reason that different parts of our reactor have different physical sizes.

The Resonance Escape Probability, p

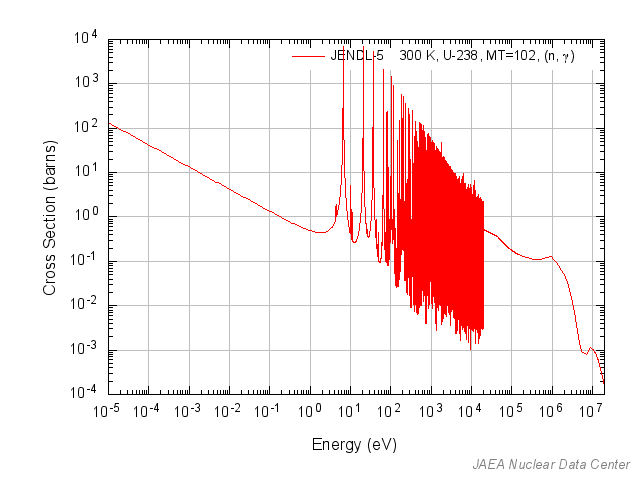

The resonance escape probability gets its confusing name from the idea that it is the probability that a neutron will avoid resonance capture. As you might recall from our discussion of cross sections at some energies large capture cross section peaks or resonances appear at energies from around 1 to 10000 eV depending on the isotope.

Now, nuclear fuel contains U235 and U238. U238 as can be seen has a lot of big capture resonances in between the fast and thermal energy regions.

As a neutron interacts with the moderator it slows down via elastic collisions, but it does not do this in one step. There are a series of intermediate steps during which it has an ‘intermediate’ energy which put it in the energy range for capture by U238. If the neutron with this energy collides with a U238 nucleus, there is a high probability that it will be captured instead of being scattered in an inelastic collision. A neutron captured is a neutron lost that could have been used for fission. Evading capture in the resonance energy range is the resonance escape probability, p. The higher p is the more neutrons make it to thermal energies unscathed where they can easily induce fission. Or to put it simply.

Now this is a tricky one to actually model. In a heterogeneous reactor you can get away with the following function, but you can get really in depth with this if you like.

In the numerator Vf is the fuel volume, Nfe is the number density of resonant fuel nuclei meaning the number density of U238, I is the effective resonance integral. Going down in the denominator Vm is the volume of the moderator, ξm is the collision logarithmic decrement (also known as the moderator slowing down decrement), Σm is the moderator macroscopic scattering cross section and I is the effective resonance integral.

Ok, so what the heck does all of that mean? Well the numerator represents the number of U238 nuclei that can suck up your neutrons as they travel through the energy range. The denominator represents the effect of the neutron moderator slowing neutrons down via scattering interactions to get them below the resonance energy danger zone Now we have two variables, ξm and I.

ξm represents the awkwardly named slowing down decrement and it represents the average energy a neutron loses after a collision with a moderator nucleus. The more rapidly a neutron loses energy, the less time it spends in the resonance region, so there is a lower chance it will get captured. I discussed this in a bit more depth here if you want a refresher.

A is the atomic mass number of the moderator nucleus. When dealing with hydrogen, ξm=1. If you’re feeling lazy you can approximate ξm like so.

The bigger the value of A the more accurate the approximation.

I is the resonance integral which integrates the probability of interaction over the resonance energy range. This means it sums up the area of the resonance peaks; the larger the peaks, the greater the likelihood a neutron will get captured before dropping below the resonance energy.

Ehigh and Elow are the bounds of the resonance region in terms of energy. Looking at our U238 graph, we see the resonance region sitting from about ~3 eV to ~12,000 eV.

Now actually calculating this integral is a royal pain in the neck. In the modern age physicists and engineers typically resort to brute force Monte Carlo computer simulations. Fortunately you can sometimes find tables of approximations or solved functions to use which are good enough for our purposes. I like this one which I found in Lewis (2008)10 for natural uranium fuel rods with a density ρ and diameter D between 0.2 and 3.5 cm.

Note that this bad boy will give you an answer in barns (1E-24 cm2) so don’t forget to convert it to cm2 so that the units work out properly.

The Fast Fission Factor, ε

The fast fission factor tells us the ratio of all fission neutrons produced (Both fast and thermal energy neutrons) and the thermal fission neutrons11.

So if all your neutrons are thermal, ε = 1. The more fast fission events you have, the larger ε becomes. In the case of thermal reactors though the fast fission effect is usually pretty small. As function, it looks like this (as always assuming a constant neutron flux for simplicity).

If we look at Table 1 we can find values for ν, the number of neutrons produced per fission event, in this case 2.421 for the thermal fission of U-235 and 2.655 for the fast fission of U-238.

Putting it all together, a really rough example

Now we’ve covered the for main factors in the four factor reactor equation.

At the risk of going on for far too long, let’s look at a really simple reactor design. We’ll assume a reactor moderated with graphite and fueled with natural uranium.

We start by calculating all the variables and we’ll start with the neutron multiplication factor. As we only care about the relative isotope ratios in this calculation, I’m just multiplying the cross section by the enrichment ratio and the number of neutrons per thermal fission of U-235. As U-238 has no thermal cross section the U-238 term is zero.

Moving on to the thermal utilization factor; in this example we’re not considering a control rod, only a moderator and fuel so the function for f is slightly simplified. Also, we’ll just make an estimate of the volume ratio between moderator and fuel instead of doing a more complicated geometric analysis. Let’s say a 1:100 fuel to moderator volume ratio meaning that for every volume unit of uranium fuel there are 100 volume units of graphite moderator. Now we have to find the number ratio between the atoms of fuel and atoms of graphite. To find these we start with our cross sections for capture in fuel and moderator. Remember, our fuel capture cross section includes the weighted sum of the U-235 and U-238 cross sections like we used above.

For graphite I just looked up the capture cross section on a table.

Now we need to find the number density for the moderator and fuel. Note that we’re not finding the actual number of atoms we’ll use in our reactor; rather we just want to find the ratio between the numbers of atoms in a given volume and then modify them using our fuel to moderator ratio.

We use 238 as our A value because the amount of U-235 is negligible in natural uranium. Turning to graphite, which is entirely carbon, we find this value for the number density.

The reason for a 1.6 g/cm3 density is because I’m assuming reactor graphite, which is a specially prepared, highly pure graphite used in nuclear reactors12. We multiply the moderator by 100 because of our fuel to moderator ratio. Next we find the macroscopic cross sections.

Then we put these into our thermal utilization equation we find f.

Next we have to grab the resonance escape probability. First we’ll find ξm for graphite.

As we don’t yet have a fuel geometry we can’t yet use our geometric approximation for the resonance integral I. So I looked up a table of resonance integral approximations in Lewis (2008) and used that.

For the number density of the fuel, we simply use the value we calculated above as nU. Putting it all together we find p.

Finally we come to our fast fission factor.

Now we can bring it all together.

At 0.908 our hypothetical reactor is subcritical. The reaction will die away and a chain reaction cannot be sustained. We’re close though. This is how the first reactor was built, as fuel and pure graphite became available smaller sub-critical assemblies were built, measurements of neutron activity were taken and k was derived as Fermi, Szilard and their team walked towards the first critical reaction.

Next time I’ll go over ways we can improve this simple model and provide some worked examples so we can better understand how these elements play together. We’ll change the fuel and moderator ratios, deal with physical masses and volumes, get into fuel geometry and see what it will take to make a reactor core sustain fission. I’m also going to introduce the concept of neutron diffusion, which is a bit tricky if you haven’t seen a differential equation before but it will help lay the groundwork for concepts we’ll need when considering big explosions. Anyway, thanks for reading.

Kuroda, On the Nuclear Physical Stability of the Uranium Minerals, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1956; How this paper didn’t win a Noble Prize after the phenomena it predicted was discovered is beyond me.

Szilard became a molecular biologist following the Second World War and became involved in nuclear arms control discussions. He’s a fascinating character and I recommend Lanouette’s Genius in the Shadows if you’re interested in his life and times.

See Szilard and Zinn, Instantaneous Emission of Fast Neutrons in the Interaction of Slow Neutrons with Uranium, The Physical Review, Volume 55, No. 8, April 15, 1939

I want to note that when we get to bombs, scattering and escape out of the fuel mass become much more important as the time scales become much, much shorter, but for now, with thermal energy neutrons we only need to worry about fission and capture. Fission in this case of uranium-235 and capture in uranium-238. Of course as we have discussed U-238 can undergo fast fission if the neutron has enough energy to begin with, but at thermal energies the likelihood of a neutron inducing fission in U-235 becomes much higher.

Reed, Physics of the Manhattan Project; Second Edition, Springer, 2011; This book also explains the k derivation very well.

Yes I know there are more isotopes in a given mass of uranium than just 235 and 238; traces of 234, spontaneous fission products and other oddities but that just complicates things for this example.

Heavy water is just water where the hydrogen in the water molecules is almost entirely deuterium as opposed to ordinary hydrogen. This water thus weighs more, hence the name. Unlike ordinary hydrogen, deuterium has a much lower neutron capture cross section, so parasitic neutron capture events are much rarer when compared to ordinary water.

Lewis, Fundamentals of Nuclear Reactor Physics, Academic Press, 2008. This book is very useful with helpful derivations. The problem set solutions are also helpful if some of the mathematics seems a bit out there.

Resonance fission is essentially negligible because the U-238 capture cross sections at resonance energies are much larger than the fission cross sections of U-235 in the resonance region; any neutrons that could cause fission get hoovered up by U-238.

Kim, Song et al., Porosity of Nuclear Grade Graphite, Transactions of the Korean Nuclear Society Spring Meeting, 2012. If you’re curious about reactor graphite.